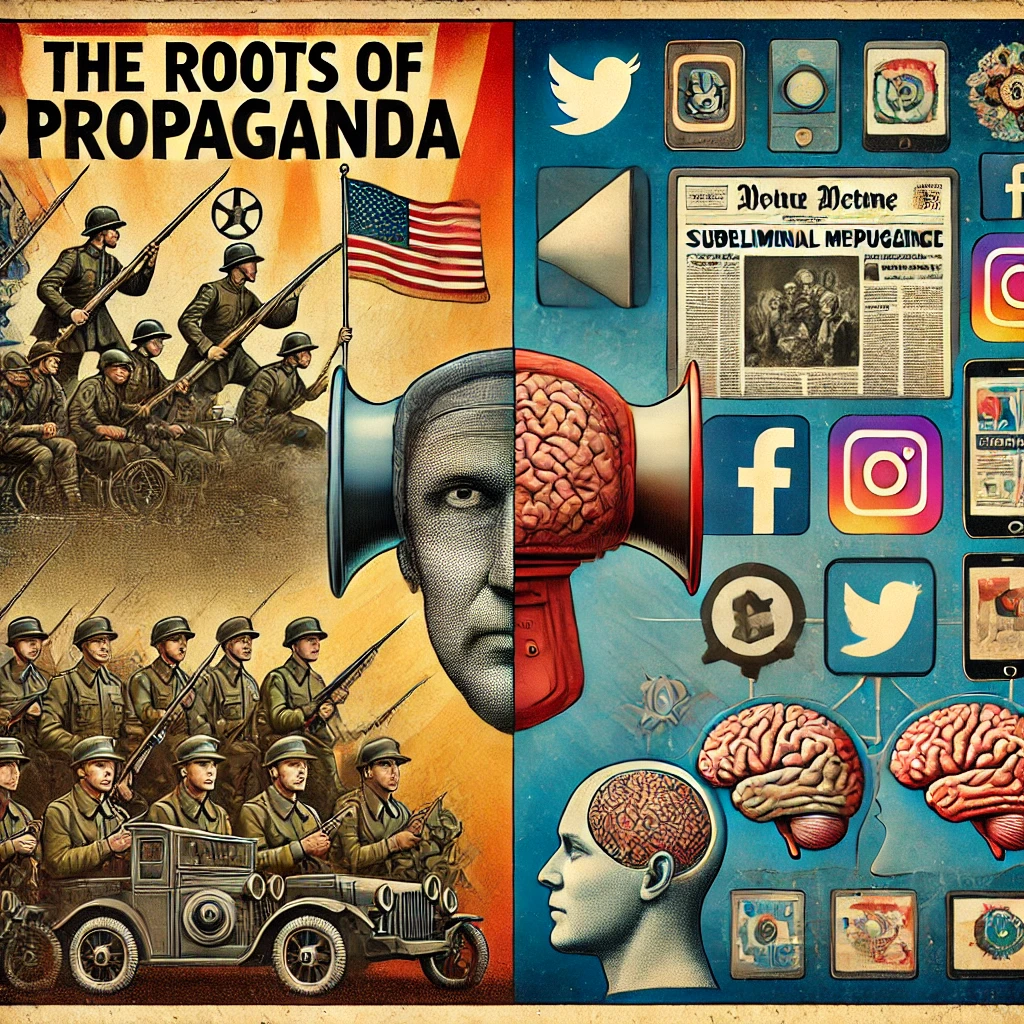

The Evolution of Propaganda: From War-Time Influence to Modern Dark Marketing

Propaganda has long been a powerful tool of persuasion, used to shape public opinion, mobilize support, and reinforce ideological control. While often associated with wartime manipulation, its evolution has led it beyond the battlefield into advertising, branding, and consumer influence, where it operates under different names but retains the same fundamental purpose: to engineer perception and behavior.

This transition—from state-driven wartime propaganda to corporate dark marketing techniques—has not only changed the way people process information but has also raised critical ethical concerns. The modern consumer landscape is saturated with psychological manipulation tactics, many of which are descendants of the very same strategies that once fueled nationalistic fervor and wartime unity.

The Foundations of Propaganda in War and Politics

The earliest refined uses of propaganda were not found in advertising or business but in the strategic operations of war and political control. Governments quickly realized that influence over public perception was just as crucial as military strength.

World War I: Mobilization Through Messaging

During World War I, governments used mass media to create a sense of national duty, urging citizens to support the war effort, enlist, and conserve resources. One of the most iconic examples is the “Uncle Sam Wants You” poster designed by James Montgomery Flagg, which framed military enlistment as not just a duty but a personal obligation to the nation.

World War II: Psychological Warfare and Ideological Conditioning

By World War II, propaganda had evolved into a highly sophisticated mechanism of psychological warfare. The Nazi regime, under the direction of Joseph Goebbels, used radio broadcasts, film, and mass rallies to build a cult of personality around Adolf Hitler and reinforce racial ideologies. Meanwhile, the Allied forces countered with their own propaganda, framing the war as a battle for democracy against authoritarianism.

Governments also manipulated media content to control narratives. Hollywood films were co-opted as tools of persuasion, embedding nationalistic themes into their storytelling. In Britain, the Ministry of Information closely collaborated with filmmakers to craft morale-boosting content that ensured public support for the war.

The Shift from War to Commerce: Propaganda as a Business Strategy

As global conflicts subsided, propaganda did not disappear—it transitioned into the world of commerce, marketing, and consumer persuasion. This shift was spearheaded by Edward Bernays, a pioneer in public relations who applied wartime propaganda techniques to advertising and brand management.

Bernays, influenced by his uncle Sigmund Freud’s psychological theories, argued that consumers were not rational decision-makers but emotional beings driven by subconscious desires. By tapping into these psychological impulses, businesses could manufacture demand not by selling products, but by selling identities, aspirations, and fears.

Bernays’ approach was revolutionary:

- He successfully rebranded cigarettes as symbols of female empowerment, encouraging women to smoke as an act of independence.

- He transformed breakfast culture in America by promoting bacon and eggs as the “ideal” morning meal, despite no inherent nutritional superiority.

- He helped corporate giants like General Motors and Procter & Gamble cultivate long-term consumer loyalty by embedding psychological triggers into brand messaging.

This marked the beginning of corporate propaganda, where advertising stopped being about selling products and became about engineering perception at a mass scale.

The Rise of Dark Marketing Tactics

As advertising techniques became more sophisticated, they also became more manipulative, blurring the ethical boundaries between persuasion and coercion. Some of these tactics, derived from wartime psychological operations, have been rebranded as “marketing strategies” but retain the same core principles of influence, repetition, and cognitive exploitation.

Subliminal Messaging: The Manipulation of the Subconscious

Subliminal messaging involves embedding hidden cues within media that bypass conscious awareness but influence decision-making at a subconscious level.

- In the 1950s, researcher James Vicary claimed that flashing subliminal messages such as “Eat Popcorn” and “Drink Coca-Cola” during movie screenings increased sales. Though later debunked, the experiment sparked a global debate on the ethical implications of subconscious persuasion.

- Today, brands use neuromarketing techniques to subtly guide consumer behavior, such as placing products at strategic eye-level positions in stores or using color psychology in packaging to trigger subconscious associations with trust, urgency, or comfort.

Fear-Based Advertising: Exploiting Anxiety for Profit

Fear is one of the most powerful motivators, and many industries use fear to drive consumer action.

- Insurance companies leverage fear of financial ruin, natural disasters, and health crises to encourage policy purchases.

- Health campaigns frequently use graphic imagery of disease or injury to promote safer behaviors, such as anti-smoking campaigns featuring images of lung disease.

- Political campaigns use fear of economic collapse, national security threats, or social unrest to steer voter behavior.

While fear-based advertising is undeniably effective, it raises serious ethical questions about the long-term psychological impact on audiences.

Shockvertising: The Power of Provocation

Some brands opt for shock tactics to grab public attention, using disturbing, controversial, or provocative imagery to create viral conversations.

- Benetton’s controversial ad campaigns, which featured graphic depictions of AIDS patients, interracial couples, and war zones, aimed to challenge societal norms while keeping the brand in global headlines.

- The anti-drug movement has used images of physical decay and social ruin to deter substance abuse, banking on the shock factor to create lasting impressions.

While these campaigns are effective in sparking discussion, they can also backfire if perceived as exploitative or insincere.

Guerrilla Marketing and the Influence Economy

Modern propaganda is no longer confined to government agencies or corporations. The rise of social media and influencer culture has decentralized propaganda, making it more pervasive yet harder to detect.

- Guerrilla marketing, an unconventional and often unexpected form of advertising, uses street art, staged events, and viral challenges to create buzz.

- Influencer marketing has become one of the most insidious forms of propaganda, as followers often perceive influencers as authentic, relatable figures rather than paid advertisers.

- Astroturfing, or fake grassroots campaigns, manipulates public perception by creating artificial trends, movements, or outrage campaigns to sway consumer behavior.

The fusion of AI-driven content curation, behavioral tracking, and micro-targeting has made propaganda more precise than ever before.

Ethical Implications and the Future of Influence

As propaganda techniques become more sophisticated, subtle, and embedded within everyday experiences, ethical concerns continue to grow.

- Should companies be required to disclose their psychological manipulation tactics?

- Should governments regulate AI-driven content personalization to prevent mass misinformation?

- How can consumers protect themselves from becoming passive recipients of engineered narratives?

In the coming decades, propaganda will not be about convincing people of a single truth but controlling the entire information ecosystem in which truths are formed. The ability to recognize and dissect propaganda will be the defining skill of the modern age.

Conclusion: The Power of Narrative Control

From wartime messaging to corporate marketing strategies, propaganda has never been about delivering information—it has been about controlling how information is perceived. Those who understand its mechanics shape reality itself.

As media, technology, and artificial intelligence continue to evolve, so too will the sophistication of persuasion techniques. The question is no longer who controls the message, but who controls the infrastructure through which messages are received, interpreted, and internalized.

Understanding the past, present, and future of propaganda is not just an academic pursuit—it is an essential skill for navigating a world where influence is currency, and perception is power.